research

I use models to research how physics affects the transport of material around the coast.

Selected projects:

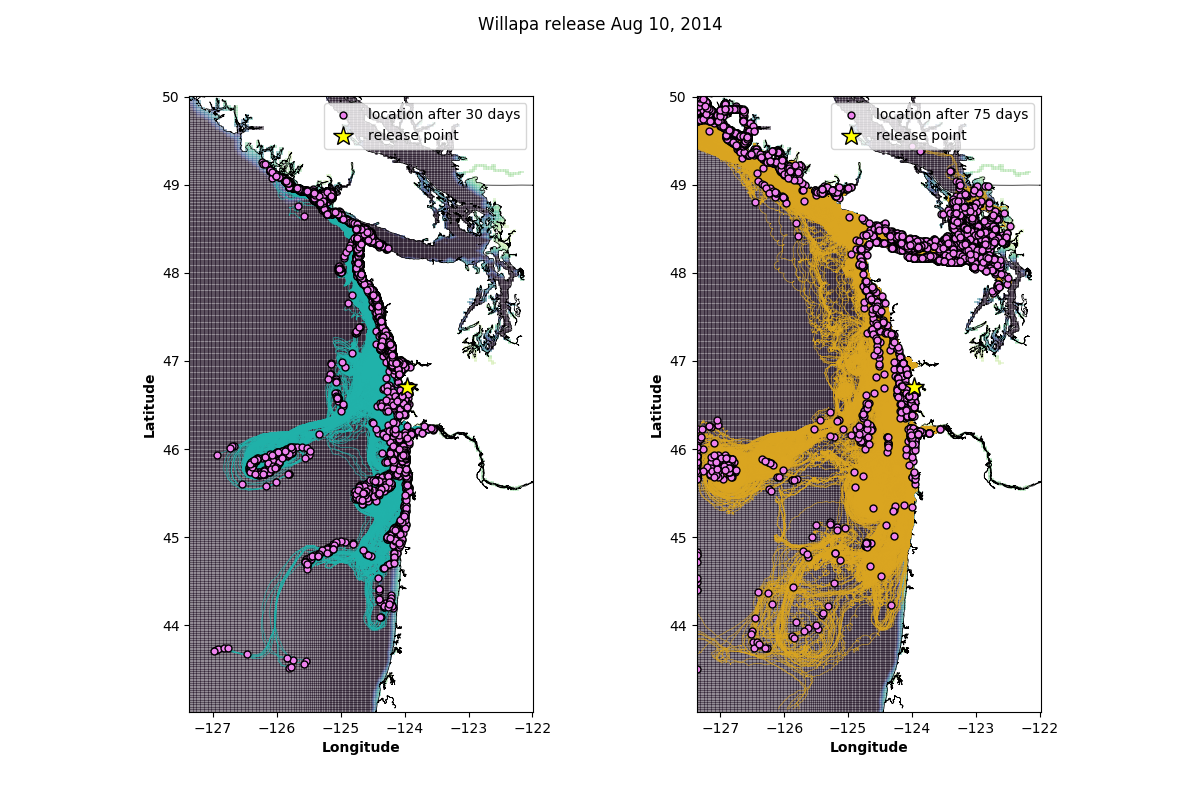

Green crab invasion pathways

European green crab is a destructive marine invasive species that preys on softshell clam, outcompetes local crab species, and destroys eel grass habitat. European green crabs had been present in bays on the coasts of Washington and west Vancouver island since 2000, but despite rigorous monitoring, they were only found in the eastern Salish Sea in 2016. Why now? The strongest hypothesis was the accidental antrhopogenic introduction of European green crab into Sooke Bay in 2011, but Sooke Bay is situated at a westward current that would have made it difficult to crabs to spread further east. Could we really rule out the infested bays along the Washington and Vancouver coasts? I teamed up with Washington Sea Grant Crab Team to investigate possible ocean current pathways for European green crab larvae in the years leading up to 2016 by using a realistic numerical model of the Pacific northwest coastal ocean. I seeded the model with tracers that would follow the ocean currents passively, simulating the way larvae are swept along by ocean currents. The experiments were informed by biology (European green crab spawning patterns, diel vertical migration, and aging) and regional physics (flow reversals in the Strait of Juan de Fuca).

Publication:

Brasseale, E., Grason, E., McDonald, P.S., Adams, J., and P. MacCready, 2019. Larval transport support for identifying population sources of European green crab in the Salish Sea. Estuaries and Coasts 42 (4), DOI: 10.1007/s12237-019-00586-2. link

Shelf inflow to estuaries

Estuaries are rich environments that are homes or nurseries to many species, including economically important species like oysters. Typically, estuaries are thought to accumulate pollution from land runoff and detritus from local ecological activity which is flushed out by clean ocean water. But oceanographers know that the ocean is not homogeneous - it has patches of acidic, oxygen-poor water that may be harmful to estuarine inhabitants. Here we wanted to get a better understanding of where the oceanic inflow to estuaries originates on the continental shelf (“shelf inflow”). Ocean water is drawn into estuaries because pressure is lower underneath the buoyant estuarine water. When an estuary is large enough to feel the rotation of the Earth (if the mouth is wider than the Rossby radius), then shelf inflow will have to turn left (in the Northern hemisphere) as it moves across the shelf into shallower water to approach the mouth. This is because, on a rotating planet, relative vorticity increases as the water column gets shorter. But as inflow evolves from a cross-shore current to an along-shore current, along-shore friction arises to balance the changing vorticity. The steady state analytical solution for shelf inflow when there is only an estuary tidal mixing, and planetary rotation is a current that flows in from the right of the estuary, turning to enter the mouth. This is the same side of the estuary that the buoyant river plume bends towards to form an outgoing along-shore gravity current. I tested this analytical in a series of three dimensional idealized models, using particle tracking to illustrate shelf inflow paths. The analytical solution described much of shelf inflow well, but additional details were revealed by using an unsteady three-dimensional model. Two new secondary inflow paths were identified: one of particles returning to the estuary mouth from the outflow plume, and one from the left hand side of the estuary. We also found that in some circumstances, the shelf inflow was partially overlapped by the estuarine outflow, shearing the plume front.

When wind is introduced, the result changes. The shelf develops an ambient current that flows parallel to the direction of the wind, carrying the inflow and the outflow. Thus, the inflow must come from the upwind side of the estuary, while the outflow flows downwind. The surface and bottom layers of the ocean move perpendicular to the wind, because planetary rotation turns accelerating currents to the right as they speed up (the surface) and to the left as they slow down (like the seafloor). At the U.S. west coast for example, when wind blows to the south (called upwelling-favorable wind), surface water is carried offshore and bottom water is carried onshore. The exchange of surface water for bottom water means coastal waters will become colder and more nutrient rich during upwelling-favorable wind. Using particle tracks again to visualize shelf inflow, I tested the effect of wind stress on shelf inflow to estuaries in both idealized and realistic models. We confirmed that shelf inflow originates on the upwind side of the estuary mouth, but also demonstrated that the source water for shelf inflow is denser and relatively deeper during upwelling-favorable winds.

Publications:

Brasseale, E., and P. MacCready, 2021. Shelf sources of estuarine inflow. Journal of Physical Oceanography 51, DOI: 10.1175/JPO-D-20-0080.1. link

Brasseale, E. and P. MacCready (in progress). Effect of seasonal wind stress variation on the source of shelf inflow to the Salish Sea and Columbia River estuary.

Wave-driven transport of nearshore wastewater pathogens

In the San Diego-Tijuana area around the United States-Mexico border, inadequate infrastructure at the San Antonio de los Buenos wastewater treatment plant (SABWTP) spills tens of millions of gallons a day of untreated wastewater onto the beach. This creates a water quality hazard that can spread to recreational beaches up to 30 km away because wave-driven currents travel easily along the straight, sandy coastline. Waves are conserved until breaking in the surf zone, and currents driven by breaking waves are the biggest currents in the nearshore. Therefore, we hypothesized that we could model the location of the wastewater plume along the beach based on waves at an offshore buoy. This one dimensional model with only one forcing input was tested by seeing how well it could reproduce the distribution of dye (simulating wastewater) at regional beaches in a 3D ocean-wave coupled hydrodynamic regional model over the course of a year. In particular, we looked for times when dye concentrations were high enough to merit a beach advisory. The 1D nearshore model agreed with the hydrodynamic model on 89% of all time steps at all locations. This gives us confidence that a simple model could be used to help predict water quality problems stemming from the SABWTP at regional beaches. You can see movies of the hydrodynamic model and some validation work on the project page.

This is ongoing work. What we’re interested in next is testing different dye decay algorithms to represent the way different pathogens in wastewater react and inactivate. This would demonstrate the difference between the pathogens that are tested for in water quality sampling, called fecal indicator bacteria (FIB), and those that are most likely to make beach goers ill. Unfortunately, FIB die off faster than norovirus, for example, which is abundant in raw sewage and very likely to cause gastrointestinal illness if accidentally ingested. By modeling FIB and norovirus, we can demonstrate how often a negative FIB result elides the presence of other wastewater pathogens. Modeling FIB is also necessary for comparisons with historical water sampling data, which will enable validation beyond the model-model comparisons done in the first study.

Publication:

Brasseale, E., Feddersen, F., and S.N. Giddings, (submitted). Performance of a one-dimensional model of wave-driven nearshore alongshore tracer transport and decay. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.